Monet’s doubts at Giverny

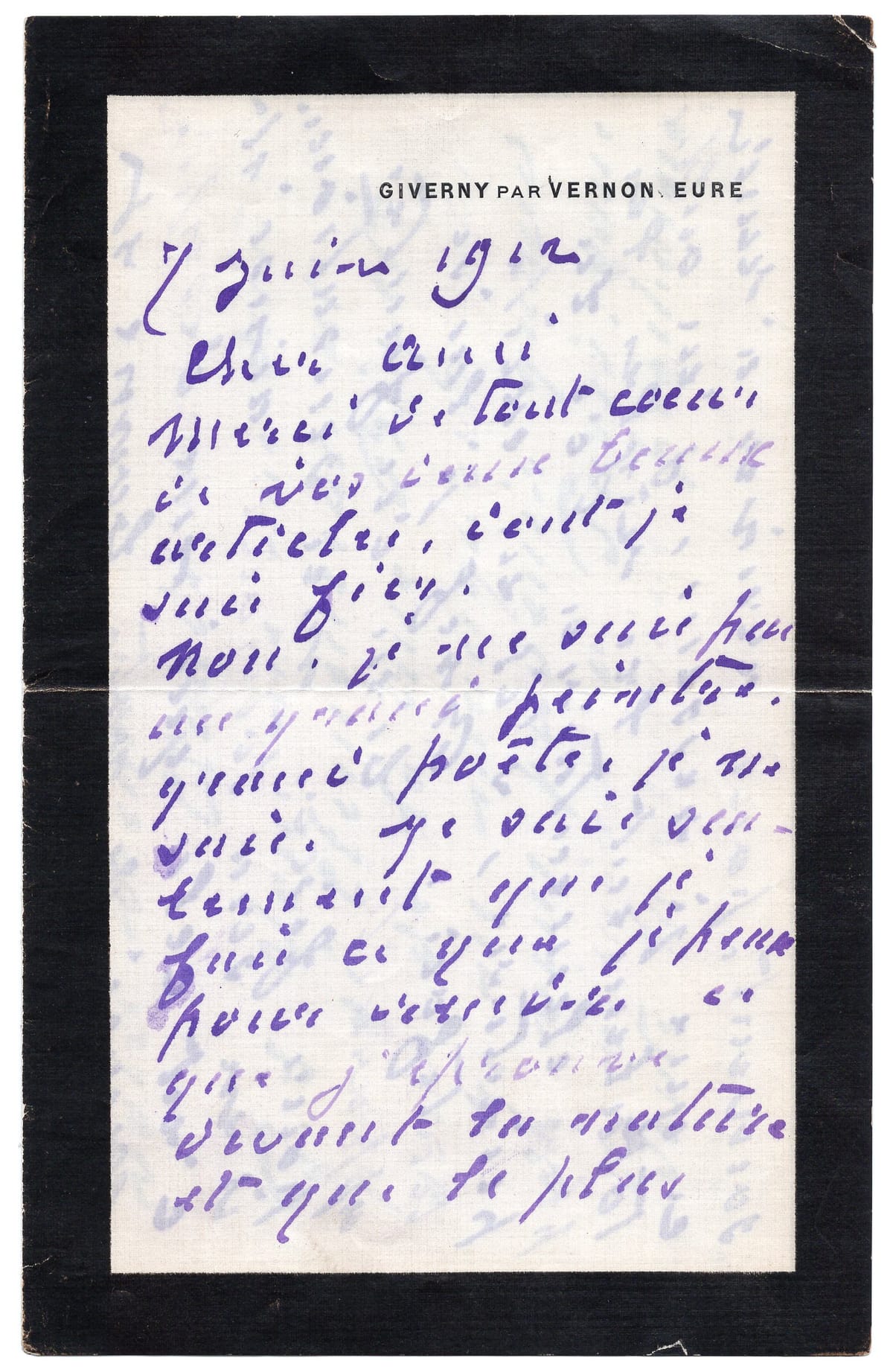

In June 1912, Monet, troubled by cataracts, painted fervently in Giverny and wrote a humble, emotional letter to Gustave Geffroy. Doubting his talent, he prioritized feeling over form. A touching postscript reveals his deep friendship with Georges Clemenceau.

In June 1912, despite the growing discomfort caused by cataracts, Claude Monet painted tirelessly in his beloved gardens at Giverny. His brush moved across the canvas to capture the arches of roses, the shifting reflections of water, and the soft architecture of his flowerbeds. These were not yet the monumental Nymphéas of the Orangerie, but the seeds of that vision were already taking root. In the quiet of Giverny, Monet painted against all odds, striving to render sensations rather than scenes.

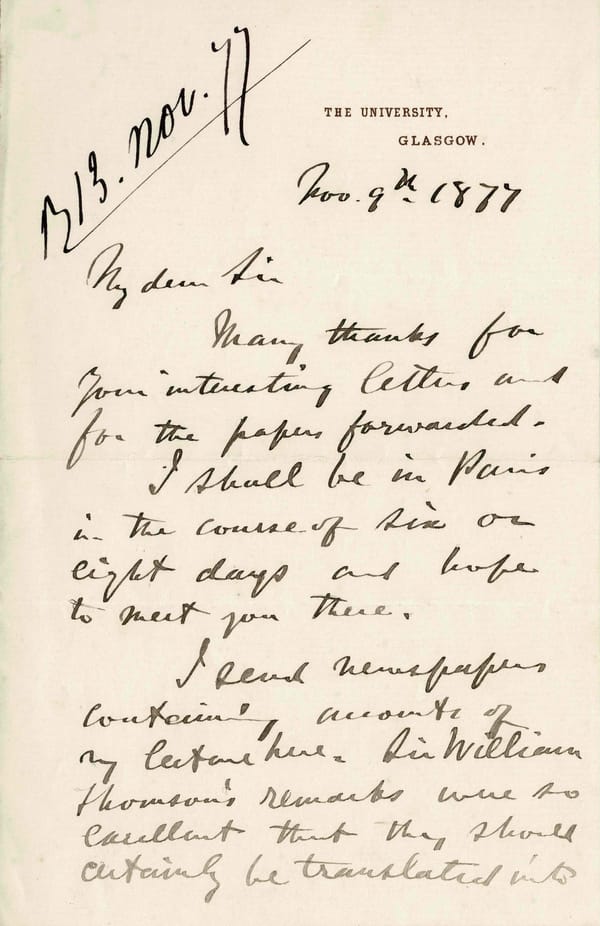

It was in the midst of this intense creative period that Monet took up his pen to write to his friend Gustave Geffroy, a journalist, art critic, and longtime confidant. Geffroy played a key role in Monet’s life and growing fame, his monumental monograph on the artist remains a landmark. In fact, most of the Monet letters available on the market today come from their long and rich correspondence. In response to what appears to have been high praise, Monet displayed striking humility:

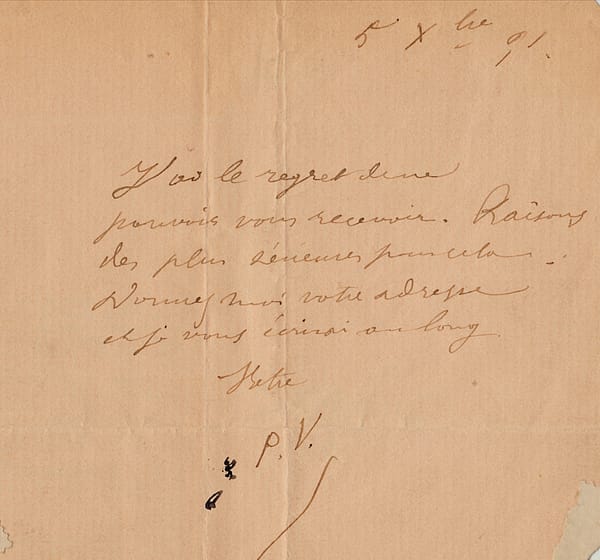

No, I am not a great painter. A great poet, I do not know. I only know that I do what I can to render what I feel in front of nature and that most often, in order to render what I feel, I totally forget the most elementary rules of painting, if there are any. In short, I let many mistakes appear in order to fix my sensations. It will always be like that and that is what makes me despair.

This confession goes beyond modesty, it offers a rare glimpse into the mind of an artist who prioritized emotional truth over academic precision, and who wrestled with the limitations of his own pictorial language. Written in Monet’s signature purplish ink on mourning paper - his wife Alice had died just a year earlier - this brief but poignant letter will resonate with anyone who has ever doubted their talent while remaining fully devoted to it.

As a postscript, a touching detail:

You have not told me whether Clémenceau has left the rue Bizet.

He was referring to Georges Clemenceau, Monet’s closest friend, whose political and personal life often intertwined with that of the painter. Introduced by Geffroy in the 1890s, their friendship deepened after Clemenceau published a glowing article on Monet’s Rouen Cathedrals. By 1912, Clemenceau was already a central figure in the French Republic, six years before leading France to victory in World War I and earning the nickname “Father of Victory.” At the time of this letter, Clemenceau had just undergone surgery, and Monet’s concern is simple, almost domestic: has his friend stepped outside?

This letter is shared by Laurent-Maria Deschanel, a French expert and founder of Autographes.com. A respected autograph dealer, he offers a refined selection of original letters, manuscripts, and signatures from renowned figures around the world — artists, writers, scientists, political leaders, and more. Guided by his passion and discerning eye, the website features a rich, carefully curated, and regularly updated thematic catalog.